This week in class we read an article by Al Kaszniak entitled “Contemplative Pedagogy: Perspectives from Cognitive and Affective Science”. Kaszniak makes an argument for the importance of contemplative practices for higher education, based on their ability to help the student focus attention, shift attention from distractions, and attenuate emotional disruptions due to encountering emotionally arousing events. These three things all seem particularly important to the work that my students do in mathematics classes; they have to be able to maintain sustained focus, to focus on the salient features of a problem, and to be able to cope with the frustration that they encounter as they work mathematics problems.

I disagree somewhat with the recommendations of Kaszniak where he would like to see more controlled studies on contemplative pedagogy; I think that what would be more interesting would be to do in-depth interviews with students who participate in contemplative pedagogy to learn about the impact that it has on them and to find out the significance it has for them. My own work in education focuses on why we should be skeptical of randomized controlled trials for education; in this case, it seems like including contemplative practices is more an issue of values than an issue of scientific efficacy, and I’m hesitant to call for more “rigor” in the study of these practices.

The second article that we read was by Lutz et al., “Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness: An Introduction.” This article offers extended descriptions of what various types of meditative practices entail. The article, though, I think overrelied on Vipassana and Tibetian traditions; my own practice is in the Zen tradition, but they have just a brief paragraph about that saying, well, you know, it’s a lot like the other two. What I did find particularly helpful from this chapter, though, was the protocol on page 518 for interviewing meditative practitioners about their style of meditation; these questions, such as “Does the practice employ any discursive strategies, such as recitations?” and “Is there one object or many objects in meditation?” seem particularly important for attempting to do research on a contemplative practice.

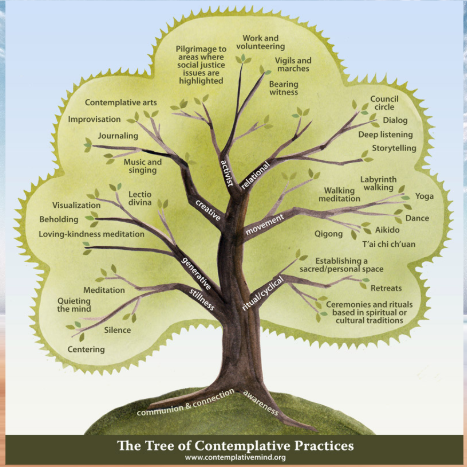

The second article leaves me with the question: what about other forms of contemplative practices besides Buddhist meditation? Particularly popular right now with people of all ages is more movement oriented mindfulness practices, and where do these fall into these schemas? I also am left a little unsettled at the idea that we can reduce spiritual experiences down to what happens on fMRIs; I know in the field of education that fMRIs are often not considered particularly conclusive when trying to study educational practices or to diagnose educational difficulties, and again, like the previous article, I wonder if focusing more on the experiences of the practitioners would be more useful that attempting to apply the tools of science to studying meditative practices.

I also find myself wondering; if something creates a worthwhile experience in the classroom, and is in line with our values and ideals as teachers, isn’t that enough to do it in the classroom? Must everything we do as teachers be justified with neuroscience? Would we subject other practices to the same scrutiny? Is, for example, free-writing and journaling in Writing classes going to be discarded if it doesn’t measure up on the fMRI studies? Are we going to discard students working in groups in math classes just because the group work class doesn’t have higher test scores than the non-group work class? It seems to me like you can make meaningful educational arguments for using these things in the classroom without having to go to the extent of quantitative research that these two authors seem to feel might be necessary for these practices.